Plastic Pellets

A recent challenge for the shipping industry is the growing problem of plastic pellet spills.

Plastic pellets, also known as nurdles, are typically the size of a lentil and the building blocks for the manufacture of plastic goods. They are highly durable and are now found ubiquitously in the marine environment. Although considered inert in their original form, plastic pellets have the potential to be damaging to wildlife if ingested, through direct physical impacts or indirectly via the carriage of persistent organic pollutants.

Losses occur throughout the production and supply chain, with chronic losses typically stemming from land-based sources, while acute losses are the result of sudden, large-scale events, such as the accidental release of containers overboard during shipping incidents.

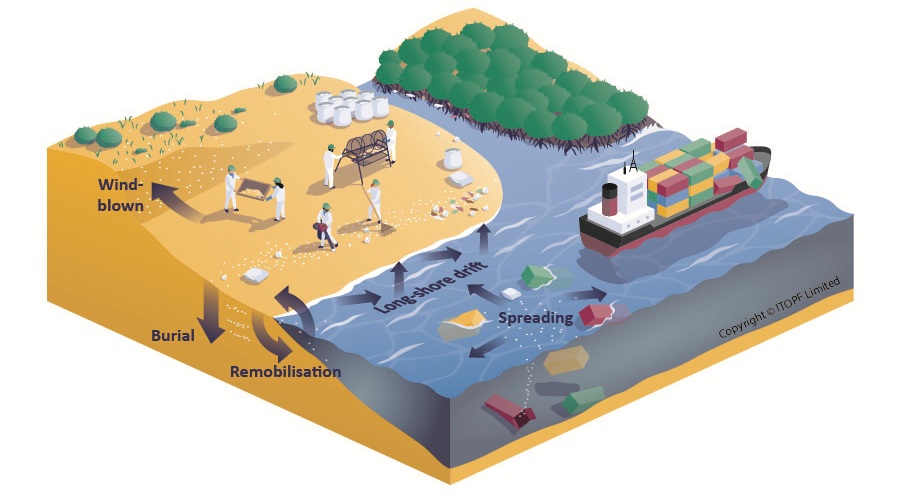

When released to sea, plastic pellets can spread over vast distances, and are extremely challenging to locate and remove. An early priority is to determine the source(s) of the pellets and, if possible, prevent further releases. The feasibility of mounting an at-sea response largely depends on whether the pellets remain in their packaging or become loose. If they stay intact, then response efforts at sea generally focus on source control, tracking, tracing and recovering the containers and/or packages. Once loose, pellets start to spread widely, in most circumstances the best course of action is to leave them to come ashore. In a port area or other situation where natural geography or artificial infrastructure limits their spread, then containment with booms and recovery with nets may be viable.

For shoreline clean-up, a rapid response, prioritising any stranded intact bags or the highest accumulations of pellets, is essential. The aim in the early stage of clean-up is to minimise the opportunity for pellets to remobilise or become buried by tidally transported sediments. Clean-up activities should be undertaken alongside continuous surveys and dynamic prioritisation.

Many of the plastic pellet response operations to date have relied heavily on low technology, manual recovery techniques, such as using shovels and buckets in conjunction with sieves or hand trommels. This is often the most effective clean-up option, as it is selective and reduces the amount of unpolluted material recovered. However, it is also labour intensive, involving sometimes hundreds of people over a wide geographic area for a protracted period. Means of mechanical recovery of plastic pellets are currently limited. They often involve adapting off-the-shelf tools and technology designed for oil spill response, such as vacuum systems, flushing or flooding systems, or heavy machinery. Due to lower selectivity, a secondary phase of separation may be necessary to avoid generating excessive volumes of waste.

Endpoints can be difficult to establish in plastic pellet cases, particularly in polluted areas. Comparing the level of residual contamination to background levels of plastic pollution (and the expectation of chronic strandings of pellets) is key to determining the appropriate level of clean-up work to be undertaken. Continuing labour-intensive shoreline cleaning operations to selectively remove small amounts of incident-related plastic pellets, is likely to be unreasonable if the background level of plastic debris is high. Suitable endpoints should be agreed by all parties involved.