Aerial Observation

movement of oil at sea.

During the initial phase of a response, aerial reconnaissance can help response personnel assess the location and extent of oil contamination and verify predictions of movement and fate of oil at sea. Once operations are underway, it provides information that facilitates the appropriate deployment of resources at sea, the timely protection of sites along threatened coastlines and the prioritisation of resources for shoreline clean-up.

Visual Observation

Visual observation of floating oil from the air is the simplest method of determining the location and scale of an oil spill.

Obtaining worthwhile results requires detailed preparation before take-off and careful interpretation of the information gathered. Helicopters are ideal for surveillance over near-shore waters where their flexibility is an advantage along intricate coastlines with cliffs. Over the open sea, there is less need for rapid changes in flying speed, direction and altitude, and the speed and range of fixed-wing aircraft are more advantageous. However, any aircraft used must feature good all-round visibility and carry suitable navigational aids.

Read more

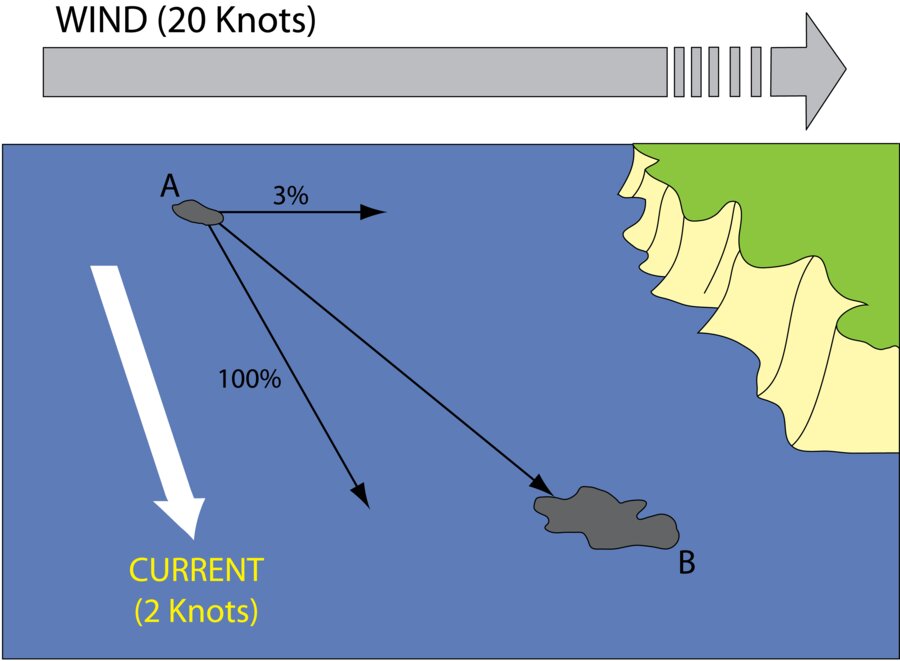

The position of oil may be predicted using wind and current data. Floating oil will move downwind at about 3% of the wind speed and at 100% of the strength of surface water currents. Close to land, the strength and direction of any tidal currents must be considered when predicting oil movement, whereas further out to sea the influence of other ocean currents predominates over the cyclic nature of tidal movement. Computer models can be used to plot oil spill trajectories, but the accuracy of any method depends on the quality of hydrographic data used and the reliability of forecasts of wind speed and direction.

It is usually necessary to plan a systematic aerial search to ascertain the presence or absence of oil over a large sea area. A 'ladder search' is frequently the most economical method of surveying an area. When planning a search, due attention must be paid to visibility and altitude, the likely flight duration and fuel availability. Floating oil has a tendency to become elongated and aligned parallel to the direction of the wind in long and narrow 'windrows' typically 30 - 50 metres apart. It is advisable to arrange a ladder search across the direction of the prevailing wind to increase the chances of oil detection.

Methods for observation and recording

Accurate observation will be assisted by having available maps and charts, and basic data such as the location of the spill source and of pertinent coastal features.

During the flight, careful annotation of the time and locations of all potentially relevant features will create a reliable record from which an informative report of the flight can be prepared. In particular, for response efforts to be focused on the most significant areas of the spill, it is important to note the relative and heaviest concentrations of oil.

GPS and other aircraft positioning systems allow the oil's location to be pinpointed. Photography, particularly digital photography, is also a useful recording tool and allows others to view the situation on return to base. Dedicated remote sensing aircraft often have built-in downward looking cameras linked with a GPS to assign accurate geographic coordinates.

Common errors

From the air it is notoriously difficult to distinguish between oil and a variety of other unrelated phenomena. It is therefore necessary to verify initial sightings of suspected oil by flying over the area at a sufficiently low altitude to allow positive identification.

Phenomena that most often lead to mistaken reports of oil include: cloud shadows, ripples on the sea surface, differences in the colour of two adjacent water masses, suspended sediments, floating seaweed, algal/plankton blooms, sea grass, and coral patches in shallow water.

Quantifying floating oil

An estimate of the quantity of oil observed at sea is important to assist planning the required scale of clean-up response.

It is therefore crucial that during the overflight the observer is able to distinguish between sheen and thicker patches of oil. Gauging the oil thickness and coverage is rarely easy and is made more difficult if the sea is rough. All such estimates should be viewed with considerable caution.

The table below gives some guidance. Most difficult to assess are water-in-oil emulsions and viscous oils like heavy crude and fuel oil, which can vary in thickness from millimetres to several centimetres.

Remote sensing

Remote sensing equipment mounted in aircraft and vessels is used to monitor, detect and identify sources of illegal marine discharges and to monitor accidental oil spills.

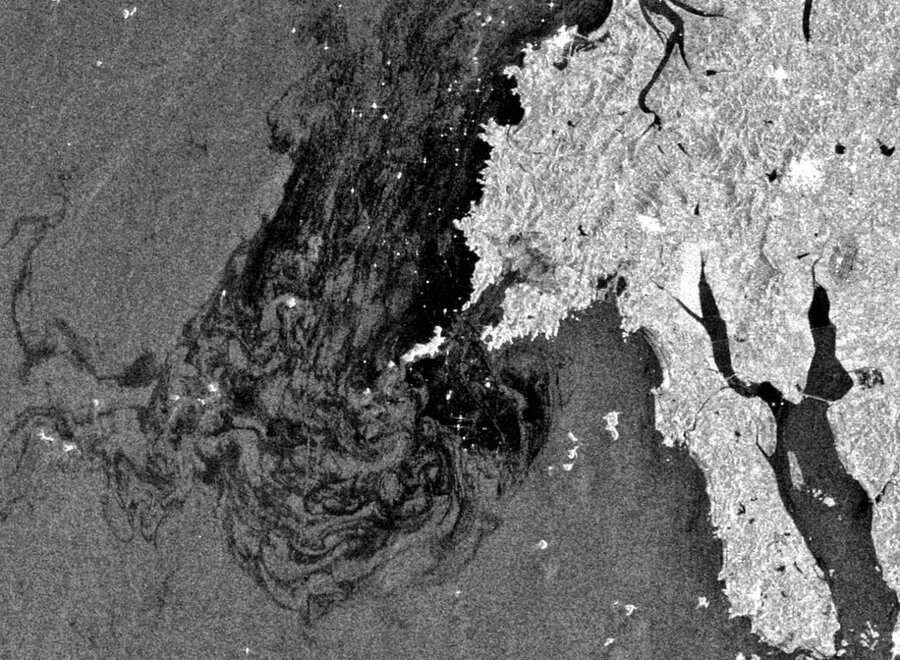

Remote sensors work by detecting properties of the sea surface: colour, reflectance, temperature or roughness. Oil can be detected on the water surface when it modifies one or more of these properties. Cameras relying on visible light are widely used, and may be supplemented by airborne sensors which detect oil outside the visible spectrum and are thus able to provide additional information about the oil. Commonly employed combinations of sensors include Side-Looking Airborne Radar (SLAR) and downward-looking thermal infra-red (IR) and ultra-violet (UV) detectors or imaging systems.

However, with remote sensing imagery, it is often difficult to be certain that an anomalous feature on an image is caused by the presence of oil. Consequently, remote sensing imagery requires expert interpretation by suitably trained personnel to avoid other features being mistaken for oil spills.

Satellite Imagery

Satellite-based remote sensing systems can also detect oil on water. The sensors on board are either optical (detecting in the visible and near infra-red regions of the spectrum) or use radar.

Optical observation of spilt oil by satellite requires clear skies, thereby severely limiting the usefulness of such systems. SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) is not restricted by the presence of cloud.